The word bureaucracy implies negativity and structure for the sake of structure, with inefficiencies and sloth-like speed. Some bureaucracy is inherent and helps preserve the organization. But when left unchecked, it becomes a negative because companies must adapt to changing times, and bureaucracy doesn’t adapt. To succeed, we need high-performing organizations that respond to customer needs rather than ones with lots of bureaucracy. Therefore, as a leader, managing bureaucracy is critical.

Bureaucratic growth occurs on two levels – on a micro level at the bottom of the organization and on a macro level at the top.

Micro Level

This level relates to day-to-day operations, such as hiring decisions and personnel. All too often, I see bureaucracy grow because of hiring mistakes. When we hire people, we have certain expectations of the person as well as what we want from that role. If the person underperforms or the job doesn’t work out, the natural tendency is to work around that mistake instead of cutting your losses. We tend to accept the deficiency of the person, the role, or the combination of the two.

When the person or role doesn’t work out, the next step is to hire someone new, maybe redefine the position, and try again. Now, the organization has two people instead of only one. Most likely, it would be better having only one person – the correct person. What happens if the second person doesn’t work out? You now have three sloths instead of one. This growth is a real problem and a detriment to the company. And if left unchecked, organizations can quickly balloon.

Another situation is rewarding good people even if it’s not beneficial to the organization. For example, you start with a certain vision, an employee steps in, and knocks it out of the park. You want to reward that person and increase their role by giving them someone to manage. Soon, bureaucracy has taken hold. A parable of this was when I wanted the grounds to look better at one of my companies. We initially hired one man to take care of the landscaping, and he did a great job. To reward him, we provided new equipment, sent him to training courses, and eventually added staff to his group. What started as a simple vision ended up adding costly resources that weren’t related to our corporate goals or core responsibilities. From the micro level, there’s always pressure to grow.

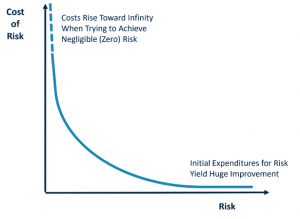

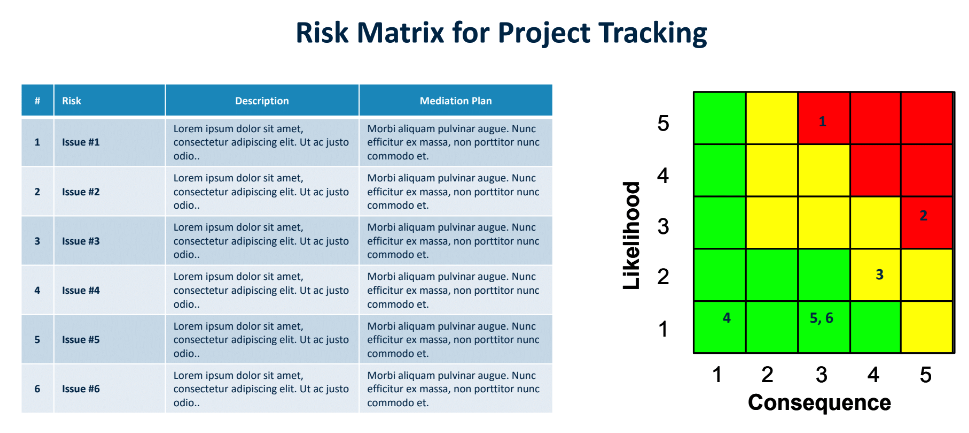

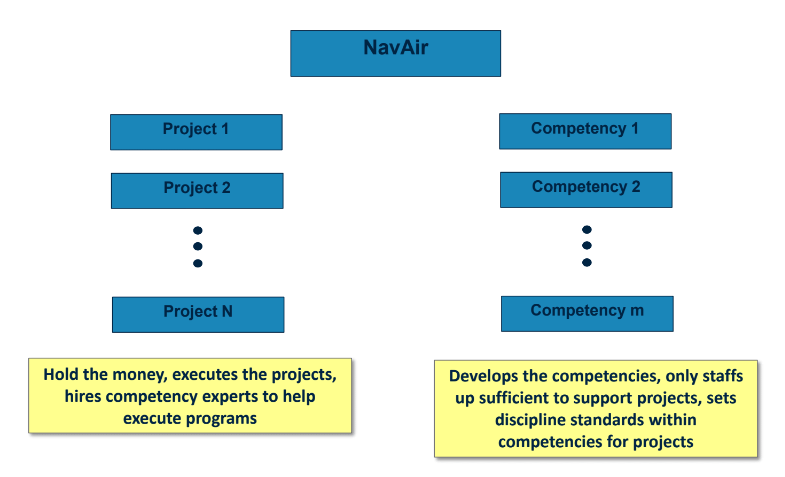

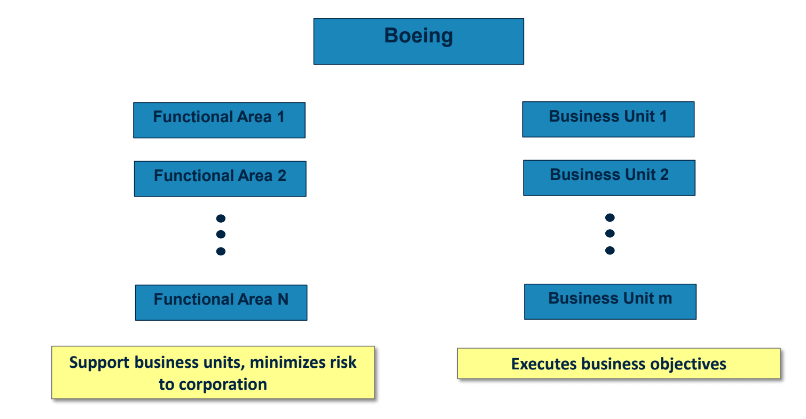

Sliwa Observation: “Good employees tend to grow their job until they believe they need staff supporting them, typically within two years of starting the new assignment.” Macro Level Organizations have a natural tendency to grow. People want to take on more initiatives and see their roles and responsibilities increase. They don’t want to be static, which puts companies in growth mode. In fact, according to the law of minimal growth, if an organization isn’t growing by 5-10% per year, then it isn’t healthy and will ultimately fail. This relates to the fact that people expect a raise each year and want to take on new projects. Following the status quo, companies need 5-10% revenue growth to cope and keep from going out of business. There are ways to address this, but organizations constantly experience this general inclination and tension. As the company adds certain functions, such as legal, finance, and insurance, they tend to promote risk aversion, and by their very nature, their goal is to reduce risk. And, this risk reduction creates bureaucracy at the macro level, slows everything down, and needs even more bureaucracy to ensure greater compliance. Another way bureaucracy grows is when an organization launches new initiatives or experiments. Inevitably, some work out while others don’t, but organizations tend not to cut off the losers or underperformers. They somehow hang around forever. Companies need to end programs that are not advancing the corporate goals. Note that this is a corollary to not replacing poor hires at the get-go. Nearly every company has an organizational chart, but I find that they promote bureaucracy because they make it easy to point out what isn’t being done. Before long, someone looks at the chart, points out a missing area, and suddenly a new role opens up. And worse than that is when someone looks at the branches and identifies a missing branch. Instead of adding one position, it’s multiple ones and new departments. Bureaucracy runs amok. When I was President of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, the staff added so much to the org chart because they limited their job description and said things weren’t their responsibility. This is a real frustration for service organizations when customers try to resolve an issue but are bounced from department to department. Ultimately, I banned the use of org charts for 18 months because the staff kept identifying things that the chart didn’t address. Instead, I passed a rule that said if an issue or problem comes up, then the person owns it, no matter their role, until the item is fixed or officially handed off to another individual. I didn’t want to hear about things “being between branches.” Nor did I allow the natural tendency of adding new functions, such as “we need a quality function, a risk function, a diversity function.” There’s lots of pressure to create new roles and functions as people identify them instead of adding them to existing job descriptions. Frequently, people say they are too busy to take on additional work, but no one goes around reassessing the work to figure out the bottom-line priorities that create space for bigger and more important initiatives. Organizations just want to add new branches, and org charts make that simple to do. Risk Aversion vs Growth In an organization, two types of people exist – value creators and asset protectors. Most people are familiar with value creators. They are the ones who create growth. Asset protectors tend to be risk reducers, such as legal and finance. Some companies even have dedicated risk departments. Almost invariably in organizations, there is a pendulum that over time swings between risk aversion and accepting risk to increase growth. For a while, the value creators are in control and try to grow the company. They take some bad risks, get exposed, create controversy, and open the company up to ridicule. Then, the pendulum swings the other way to risk aversion, generally too far. People emphasize avoiding mistakes instead of maximizing the probability of success or large wins, which is where you want your organization if you’re going to succeed. It’s a delicate balance. This is especially the case if you are dealing with venture capitalists. When the asset protectors drive the business, they come up with lots of reasons for why not to do something because it’s too risky. The company becomes stagnant. And often, the market leaves the company behind because they don’t allow the value creators to respond to market trends by looking for new opportunities and pushing the business into new areas. 3M is an organization that is really good at managing the pendulum swings and cutting off projects. They are famous for starting lots of projects, but when a project doesn’t make it, they fire off a canon in the courtyard. Tada! They announce that the project was a good try, but it didn’t make it. The team members are released so that they can work on something else. 3M cuts the losers to zero, which allows the best people to move on to other projects without a disastrous feeling. Instead, their attitude is, “Good try but on to your next project!” As a result, 3M takes pride in that 40% of its revenue comes from projects started in the last five years. They constantly rejuvenate their offerings. The bottom line is that – at both the micro and macro levels, from the top and bottom – there is tremendous pressure to increase bureaucracy, and it’s a constant struggle for organizations to keep it in check. Value of Risk Reduction Every company and project face some risk. The question is … how much do you invest to alleviate it? Initially, some amount of large risk exists, and these first risks are pretty straightforward and not too expensive to start reducing right away. But as you try to reduce it further and further, the cost of removing the risk increases asymptotically as you try to zero out the risk. It’s virtually impossible to achieve zero risk. As an engineer or manager of a project, your job is to figure out where on that curve you should be. How much risk should you absorb and where is the sweet spot with respect to the cost return you would get if you did it? In the beginning, the gains are huge, but costs increase significantly. As a result, people use things like decision matrices, also called risk cubes and heat maps, to develop a risk/cost chart. In the risk example above, the table identifies six risks. We take those risks and evaluate the consequence or impact. If something goes wrong, is it going to be disastrous or relatively benign? Then, we look at how likely it is to happen. Using these numbers, we map the risk. The green tiles are good, the yellow ones signal a warning, and the red ones are deemed really risky. The goal is to drive all risk to some level of green, not to zero, using your mediation plan. You must be willing to accept some risk as a tradeoff of reduced costs. By the way, risk matrices come in a range of designs. The one pictured above is typical for a missile project. If the project is man-rated, meaning that a spacecraft or launch vehicle will be certified as able to transport humans safely, then the chart may include an orange section or there may be a full border of red. Many variations of these exist. Anecdote 1: NavAir Naval Air Systems Command (NavAir) is responsible for delivering new airplanes and providing support for aircraft, weapons, and systems for the U.S. Navy and Marines. NavAir is a great example of an unstable organization that encourages bureaucratic growth. Let’s start with their high-level org chart. NavAir is organized around two directorates. The first is for the projects, where each project is some flying object like a plane or drone. The other directorate is for the numerous competencies, such as aerodynamics, control systems, structures, safety systems, etc. At first pass, this doesn’t seem like a bad way to set up operations. The way this works is the projects are responsible for executing the program, controlling the money, and hiring competency experts. The competencies support the projects and hire out their people to the projects. These competency groups only grow large enough to support the current projects. If you don’t have enough funding for your group, then you reduce your staff, but if you have extra funding, then you add additional resources. Since the project people know how many people they need, this becomes similar to a matrix organization. Ah, but this is the government… They’ve had so many projects come in way over budget and others with a high degree of failure that they try to reduce risk. To accomplish this, NavAir decided that the competencies were the most qualified to reduce risk. So, they put them in charge of determining the criteria needed for projects to meet the discipline standards. You can almost instantly see how unstable this is. For example, a project manager goes to the aerodynamics team and discusses the project’s needs. The competency person says that the team needs a half a person to make a first guess of the aerodynamic calculation for the vehicle. Thus, the project hires a half person. But what if the competency team says that you must conduct wind tunnel testing, test on three different computers, make 28 calculations, and fill out a notebook of data? They say that you need 10 people. You have no choice because the aerodynamic competency must sign off on your project before it can move forward, meaning the project hires 10 people. The following week, the competency representative comes back and says that a new requirement is needed. They don’t want to reduce their previous conditions, so you must hire an additional person. They come back again because they thought of something else. No! Stop thinking! Now, the team has hired 12 people. The interesting point about this is that it’s done under the auspices of focusing on requirements and not people. But in essence, they are funding their team, allowing the bureaucracy to grow. This promulgates the problem and manifests itself as falling behind schedule, increased budgets, and embarrassing situations, not to mention costly parts for customers. I had first-hand experience with this when I led Insitu and was working on a government project. I once scheduled a meeting with NavAir regarding a project that had a multidimensional aspect to it. Our entire team, which was doing all the work, had about seven people on it. But to accommodate this meeting, we had to reserve an enormous conference room because they sent dozens and dozens of people to the two-day meeting. We had to convince them all, which was time-consuming. For example, typical meetings are gate reviews where the contractor must convince the government that they completed the work necessary in order to pass the gate and continue to the next phase of the project. Image the difficulty of a small team trying to convince a much larger team that it had completed enough work to pass. Yes, they were trying to reduce risk, but it wasn’t a stable way to sustain the cost. I complained about this when I met with the Admirals, but they felt their hands were tied. They completely understood, but no one seemed to be in a position to make the break. There was a saying that none of the airplanes or vehicles built could carry the paperwork it took to create it. To prove my point of the organizational structure creating bureaucracy, I saw that sometimes there was no project director available. In these cases for modest projects, they assigned it to a competency. Management provided a budget and told them that they would be graded on whether they could complete the project. Unbelievably, the competency started waiving their own requirements because they realized it was too expensive and would make them fall behind schedule. They couldn’t follow their rules and still receive a passing grade. So, they went back and used simpler computations. But they never waived the requirements when working with projects, absolutely not. As it turns out, when the holder of the money has some influence over the requirements, then a different solution comes out. Anecdote 2: Boeing I was leading Insitu when Boeing bought us. Although the arrangements were that it was to be a wholly-owned but independent business, I remained for two and a half years for the integration. It also provided an opportunity for me to experience Boeing’s organization and processes. They are organized by business units that are responsible for achieving success. They may build small airliners, tanker aircraft, patrol aircraft, helicopters, or whatever, but they are the units that generate all the money. Like NavAir, there were also functional areas like Legal, Risk, and Facilities that supported the business units. The people from the functional areas were sometimes loaned to the business units, so they had a dotted line for reporting. But the solid reporting line was to the functional area, which makes sense because the employee’s career path remained solely with the functional area. Returning to the pendulum analogy, if it swings too far in the direction of the functional areas, it can really slow down the business if the areas judge their value based on how low they take the risk. In fact, in conversations with the CEO of Defense, now the CEO of Boeing overall, I proposed an option of driving to green instead of allowing the functional areas to drive to zero risk, especially when working with government contracts. Otherwise, it is simply too costly. But inside the company, risk matrices weren’t used at all, and the functional units tried to drive the risk for everything to zero. When we integrated Insitu, we were a small business of a few hundred employees as compared to the other groups with thousands of people. Boeing had over 100k total employees at the time, so it was an enormous operation. Even though we were relatively small, we had 42 proposed audits in the first 18 months from various functional areas. Some had good reasons, but others did not. I remember that there had been a paint spill somewhere within Boeing, and as a result, Boeing negotiated with the EPA to ensure that all Boeing units would work hard to ensure no more paint spills. With that in mind, one of the groups asked to perform an audit to see how we managed our paint. They wanted to help us drive to zero paint spills, so two people flew in to go through our procedures, processes, and paperwork as well as our reporting mechanisms. It was overwhelming, arduous to prepare everything, and an activity that consumed a lot of our time. But we agreed to do it. The next thing we knew, someone else requested the same process for oil. The requests went on and on – other hazardous materials, a group that numbered the buildings (yes, I’m serious), and facilities. It is a real problem when the pendulum swings too far in the direction of managing risk. Bureaucracy grows unchecked. Anecdote 3: Ford I’ve read this story in numerous places, but I think it bears repeating. When you have a car assembly line, the goal is to keep it functioning. If you run out of parts or have low-quality components that cause a stoppage, then it costs your company money. Ford had such a costly problem with not having the correct parts and overpaying for supplies that it developed a process that drove that risk to zero. At its peak, this functional area had about 40 people to ensure compliance. Their job was to match customer invoices to five pieces of paper. It turns out that 90% of the orders were easy to confirm, but the other 10% required more work to line up all five pieces of paper, hence the need for the additional people. This was a considerable cost. When they did a business value reengineering exercise, they decided to shift this risk burden to the vendors to have higher performance and lower costs. They told the vendors that from now on, Ford would electronically pay their invoices immediately, without opening the box or going through any verification process. The caveat was that Ford would do random quality checks, and if there was any issue with the paperwork, a miscount in the number of items, or quality issues, then they would be banned as a vendor for one year. Ford’s entire goal was to avoid shutting down the assembly line due to a lack of parts that met the quality standard. The results worked better than Ford had imagined. Vendors shipped their goods sooner because they wanted payment immediately instead of net 30 or 60 days. They usually added more parts because the risk was too high that they would be dropped as a vendor. Ford reduced the size of the department to a handful of people, inventory arrived sooner, and they ordered fewer components going forward because of the extra parts included in most shipments. Ford came out ahead. The vendor was happy with being paid quickly and didn’t mind including the extra parts because it reduced their risk. So, it was a win-win arrangement for both. Battling Bureaucratic Growth Managing bureaucracy takes a concerted effort. While it is essential for large organizations, smaller companies should keep it on their radar as they grow. Tackle the problem from both the micro and macro levels. Micro Level Macro Level At the End of the Day Organizations must grow to survive, but it has to be through a sustainable and balanced approach. If the pendulum swings too far in one direction, you will either take too many risks or your business will be sluggish and costly. Manage the company from the top and bottom, making careful and deliberate decisions to control the uncapped bureaucratic growth.

Share this Post