For most of us, negotiations are a part of doing business, with some being more skilled at it than others. What I’ve found after being at the negotiating table more times than I care to remember is that to reach a successful conclusion – creating a win-win situation – you must have an understanding of the environment. First, you must know your goals and currency of exchange, but you also need to try to hypothesize and predict the other party’s goals and what they want to receive. This advice is generic and applies to most any negotiation.

When engaging in international negotiations, however, I find that taking culture and cadence into account leads to less stressful situations. Conducting business in various parts of the world can be very different, so looking at how behavior and customs come into play puts you at an advantage during the talks. I’m also aware that the cadence of negotiations varies dramatically. So, of course, as a controls engineer, I build models of the other side to try and understand their process and the finer details. Over the years, this has reduced my stress level immensely.

My Early Exposure to Negotiations

My dad was a born negotiator, and he just loved it. His job as an international sales rep took him all over the world, but he also negotiated as often as he could. I used to teasingly say that if any neighbor ever wanted to buy a used car, he would volunteer to negotiate the deal. He was that excited by it. For me, the deals he used to work on drove me crazy because he was absolutely relentless.

So, imagine my surprise when he would return from Japan, exhausted and complaining that it was so frustrating that he couldn’t get a good deal. I remember this happening time and time again. Starting around the time I was in middle school, I remember thinking that the Japanese were tough negotiators. I knew that international negotiations were somewhat different from an early age, so I took special note of global interactions because of it. The best way to share my knowledge is to use real-world examples and a negotiation model I developed.

Observation 1: The Language Test

International discussions have an inherent problem in that not everyone may speak the same language. Even if someone speaks the language, the degree of proficiency is sometimes difficult to ascertain. I found that when dealing with Asian corporations, each had at least one person who was fluent in English. During negotiations back in the 90s, I noticed that if no one on our side of the table spoke their language, say Japanese, then one person would talk to us in English, but the others would talk among themselves in Japanese. This allowed them to have a private conversation with us in the room and for the English speaker to selectively present the best ideas.

It’s quite a different situation, however, when someone on your team speaks Japanese. In this case, everyone talks in English so that they do not have to worry about the proficiency level and how much is understood. Everyone has the same comprehension.

This behavior seemed pretty consistent throughout Asia, at least in my experience.

Observation 2: American Stereotypes

During the 90s, the Japanese were very successful and seen as a hot streak that many people assumed would blow past the U.S. and Europe. It was ultimately unsustainable, but that was the thinking at the time. One thing I observed was they admired aspects of the American culture. If I had to generalize about the way they conducted business, I would say that they tended to be homogeneous with everyone having a specific role, an enormous amount of teamwork, and little dissension or disruption.

Interestingly enough, I found that they admired aspects of the U.S. culture. They also had generalizations of Americans, such as golf courses everywhere, everyone eats giant steaks each night, the houses are all huge with large backyards where people have barbecues every weekend. When they visited, they wanted to experience our unique culture instead of going to Asian restaurants.

But what I found most intriguing was their fascination with the “cowboy” culture in business settings – the disruptions during meetings, shouting at each other, disagreements, side conversations, and that people didn’t always agree with the boss. There was open debate, in other words. From my perspective, it was the opposite of their style.

Let me share an example of a negotiation I had that encompasses these first two observations.

Negotiation Example 1: Playing the Role of Cowboy

Most of my negotiations with Asian corporations were difficult, so I tried various tactics with the intent to create a win-win situation. In a particularly tough case, I ended up using an American who was fluent in Japanese. The people sitting across the table had never met him, so they had no idea he spoke their language. The conversation followed the typical style with the primary contact speaking English to me, but when talking to his colleagues, he spoke Japanese. We took a break, and our “translator” told me that one of the people asked the lead negotiator if now was the time to demand a price decrease. His reply was, “I’ll bring it up soon.” I thanked the translator and returned to the table.

The English speaker started the conversation with a comment on how they noticed in the User Manual that there were two page 13s and no page 14. He asked what we were going to do. I had an idea and decided to try something different. I heatedly said, “We’ll re-label it!” I stood up, slapped my hand on the table, and said, “If these are the types of things we’re going to talk about, then there will be no discussion on a price decrease because this is too much to bear to be stuck in this type of minutia.” Then, I left the room and slammed the door. Needless to say, everyone was in shock, mostly my team because they had never seen me act that way.

The reaction from the Japanese, on the other hand, was unexpected. They were taking pictures and calling home to tell their spouses that they had met a real “cowboy”! And, they didn’t ask for a price decrease for six months. Pricing was not on the agreed-upon agenda, so our side wasn’t prepared to discuss it at that point. I was able, however, to buy some time by taking advantage of their stereotypes of American culture. In the end, we had a good relationship, they had a great story to share, and both sides were able to approach the future price negotiations with transparency.

Observation 3: The Cadence of Negotiations

Another common situation is conducting business over dinner or during the evening. This behavior is more standard throughout the world, but I share yet another story from Japan. At the end of most days, we would go out for the evening where we would either stay at one restaurant or go to multiple venues, one for drinks and appetizers, another for dinner, a third for another dinner or dessert, and maybe a place after that. A lot of drinking occurred and much conversation. The pattern finally stood out for me. Much of the discussion was social, but about once an hour, a business topic was discussed for about three to five minutes and, then, back to socializing. It was fascinating to see the situation play out time and time again.

I was witness to this technique being taught to a salesperson-in-training. On a business trip to meet with our trading partner, the Senior General Sales Manager, his new employee, and I went to dinner. This new hire had been in the Japanese government but was now going into sales. His English skills were excellent, but the manager spoke little English, so the young man was our translator for the evening.

Just as in negotiations, the salesman spoke to me in English and the manager in Japanese. He would speak a few minutes, then turn to me and say, “Mr. Sliwan-san, my boss wants me to ask you if you are married.” We would discuss that for a bit before he returned to Japanese. The next question was, “Mr. Sliwan-san, my boss wants me to ask you if you have children.” The conversation went like this for nearly an hour. Then, the next question was, “Mr. Sliwan-san, my boss wants me to ask you if you think there is a good sales opportunity in the aerospace industry for the software in Japan if we were to…” After a discussion, it was back to socializing with, “Mr. Sliwan-san, my boss wants me to ask you where you live in the U.S.” What was most fascinating to me was observing the senior manager train the young man in the cadence of business interactions. The goal was to have a business dinner with good social conversation, but about every hour, you bring up a business topic to keep it on track. It was a memorable experience, indeed.

Negotiation Example 2: Following Suit

This story comes from a Boeing friend of mine when he was negotiating with the Russians. I’ll call him Dan. The talks had been going back and forth for some time, and progress was being made. At one point, however, the Russians got really upset, starting pounding the table, stormed out, and slammed the door. My friend was taken aback. He had no idea what was going on. The translator told him not to worry that this was common and merely posturing and that they would return in about 30 minutes. Sure enough, that’s precisely what happened. They returned, and the negotiations continued as if nothing had occurred. Dan was flabbergasted.

The next day they met at the same table with more back and forth. Dan decided to follow their lead. He slammed his notebook down, stormed out of the room, and slammed the door. He returned 45 minutes later and sat down as if nothing had happened. They made progress, and then, the Russians order vodka, they toasted each other, and then drank. The negotiations continued over the next few days, and they ended with a good deal. If you aren’t expecting or prepared for this behavior, however, you may be shocked.

Negotiation Example 3: Strong-Arm Tactics

In the 80s, I was working at my educational software startup company, negotiating the rights for the Arab version with a “so-called” Saudi Arabian prince. I later learned that there are hundreds and thousands of princes, so how close he was to the royal family was unknown. He had reviewed our software and thought it was great and wanted to license it for the Middle East and have all Arabic translation rights. He told me that he was very busy that week, traveling and negotiating with many companies. The prince would meet with me at the end of the week, and in that meeting, he wanted my best deal. He would tell me yes or no based on that proposal because he did not want to go through a long negotiation process.

I spent the week figuring out the best deal I could make with the lowest price. Come Friday, we sat down, and I gave him my best and final proposal. He thanked me for all the preparation and then proceeded to use this as the starting point for several hours of negotiations.

I was unprepared and dumbfounded. We ended up with an okay agreement, but the results would have been better if I’d been prepared for that maneuver.

Negotiation Example 4: The Simultaneous Progression Model

When negotiating with the Japanese car company Nissan, I found myself in a long, drawn-out, frustrating process. Negotiations had been going on for months, and we had already met three times in person for a week each time and were sending daily faxes. I sent a fax before I left every night and received a reply each morning. It was so hard I couldn’t believe it. I suddenly had an appreciation for what my father went through.

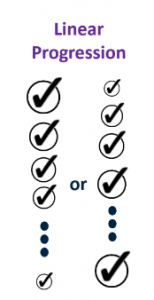

Most Westerners are taught to use linear progression as the negotiation style. Many times you walk into a room and a list is presented, and U.S. Government contracts have many pages of negotiation points. You start with either the major points and nail those and move down to the least important or knock out the most straightforward ones first and move on to the more important ones. Either way, when you reach the bottom of the list, with everything checked off, you are finished negotiating, and you have a deal. It is an easy way to organize the process.

That was the approach I used with Nissan. I started with the easiest items to address. Here’s a sample conversation:

Sliwa: What color do you want the manual to be?

Nissan: What are our options?

Sliwa: Any color you want.

Nissan: Okay, how about blue?

Sliwa: Sure, blue it is.

I check off the box and write “blue.”

Nissan: Can it be green?

Sliwa: Sure. It can be any color.

I cross off “blue” and write “green.”

Nissan: But is there any problem if it’s gray?

Sliwa: Absolutely, not. Really, it can be any color. Just tell me what you want.

Nissan: Okay, blue.

I cross off “green” and write “blue.”

Sliwa: Do you want the training classes to be two or three days? The benefit of two days is this, and for three days, it is that.

Nissan: Let’s plan for three days. But would that look better with green manuals? Let’s go back to green for the manual.

Sliwa: Alright.

I cross off “blue” and write “green” and note three days – checking off two items.

Nissan: But would green also work for two-day training classes?

Sliwa: Sure, it doesn’t matter.

This continued. No matter how hard I tried, no checkmark remained. It was very frustrating trying to corral them. But it finally dawned on me that we had different negotiating models. Eventually, I figured out that they think about the world as a circle instead of a line. That’s when I came up with the model of simultaneous progression.

They were afraid that if they agreed to any single point, then they wouldn’t get the full benefit on another point. In a sense, they tried to make that circle as small as possible by pushing on all the checkmarks and trying to find out where the degrees of freedom are. They wanted to get that circle to a place where the area under the curve was as small as it could be.

It was nearing a year into the negotiations, and I had made about as much progress as I could. As the Head of Projects, I went to the CEO and Founder of Nissan and explained that the circle was as small as we could get it and we could not do any better. He agreed and supported my decision. I sent another fax saying that the circle was as small as possible and if it were any smaller, then it would cost too much and wouldn’t be a good partnership.

The next morning, I received a fax with the message, “We received your April Fool’s fax.” What? They thought I was joking? Taking a step back, I realized the day before was April 1. Their second page said that they accepted our terms. The continued by saying that although they weren’t sure it was as small as possible, if I said it was, then they agreed. The deal was signed within two weeks. The arrangement continued for five years. I had left the company before the conclusion, but I hear that it was an excellent relationship.

Most Westerners are taught to negotiate using a linear model, and it can be surprising to find others using a different approach. Thus, I developed this model to keep myself from being discouraged.

Currently, the U.S. is frustrated trying to negotiate with North Korea on a variety of issues related to their defense posture. I notice that the U.S. media and pundits seem to have trouble because North Korea won’t start checking things off a linear list. I might argue that they see it as a circle, and we have a mismatch in expectations, style, and cadence, at least as reported by the press.

Linear and circular negotiating models do not match. If used, both sides will feel frustrated. But if one organizes around their approach, it will work out. When starting a negotiation, keep the following in mind:

- Understand the goals for each side

- Develop a currency of exchange

- Understand any cultural aspects

- Recognize the pace and cadence

An Aside

When I was negotiating with a different Japanese car company, I tried to inject humor. They had a list of discussion points, so I thought we were using a linear progression. We finally made it to the final item. Line 13: Price

Japanese: Mr. Sliwan-san, we have a real problem with the price, and we think it is important to discuss.

Sliwa: Great! Is the price too low or too high?

They spoke among themselves in Japanese for several minutes.

Japanese: It’s too high.

Sliwa: Oh, good. Now, I know what we need to talk about.

I thought it was humorous, but obviously, they didn’t see it that way. I guess since it was a tense time, American humor didn’t work.

Share this Post