As the former CEO from 2001 to 2011 of Insitu, a drone company, I am often asked for advice on how to structure a drone business. We started at a time when there were several hundred drone businesses – we called them UAVs then – and fought our way to being one of the top five with revenue approaching $500 million. We had a modicum of success because we timed it right in terms of maximizing our growth rate within a time of high military need.

Now, many multitudes of start-ups exist as the civilian markets are hoping to be unlocked in the coming years. As people have sought me out for my perspectives, I’ve heard some pretty wild ideas, including some innovative approaches. As you expect, there is plenty of overlap, redundancy, and inefficient approaches currently in the offing. Given a large number of new businesses/competitors, it seems prudent to understand and optimize the key ways to deliver value. What follows is a thumbnail sketch of the advice I offer, focused on how to structure the business value delivery chain to maximize the probability of success.

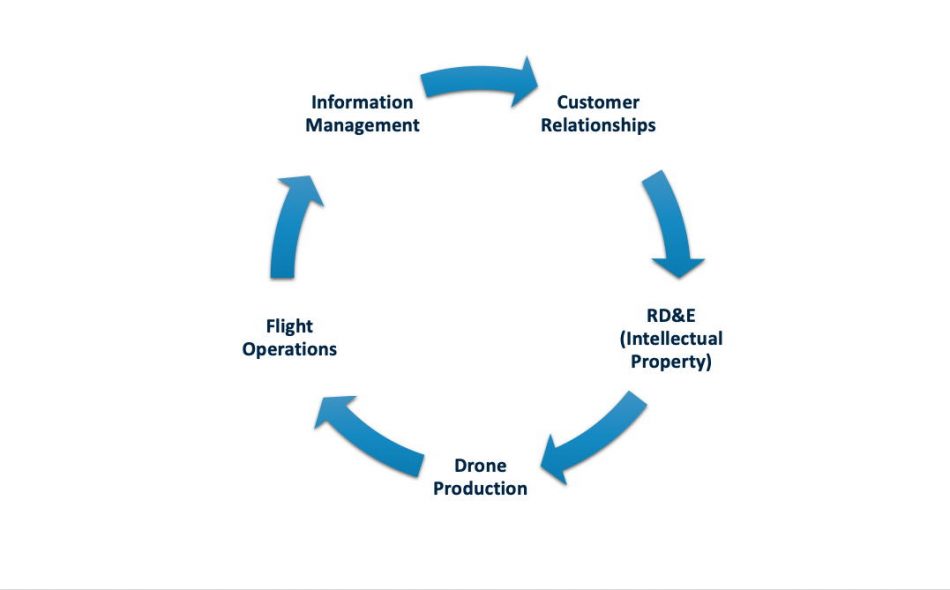

The graphic accompanying this article depicts the 5 key elements in the value delivery chain for the drone business segment:

- RD & Engineering. This stage is where new technologies are tested, validated, and refined. It’s also where technologies are readied for manufacture.

- Drone Production. This stage is where the drones, ground stations, launchers, retrievers, sensors, and communication devices are either manufactured or assembled into final systems.

- Flight Operations. This stage includes training, flight operations, regulatory compliance, maintenance, and logistics.

- Information Management. This stage is where data from the sources are collected, prepared, and managed for its ultimate purpose. A key part is finding the best ways to transform data into information.

- Customer Relationships. This stage focuses on the ultimate end-user customer relationship, the one who puts in the compensation from outside the chain and is the prime value determinant. All the other stages are funded by this customer in a steady state, not counting various forms of venture investment.

One of my most important observations is that it is virtually impossible to build a company that is world-class in every part of this value delivery chain. So, each team attacking this market must determine which part of the chain they want to own and which part they want to outsource or partner.

For example, at Insitu, we were fully integrated and used our partnerships to pretend that we did every phase. But, in reality, we partnered on R&D; outsourced virtually all production, except final assembly and test; and partnered on operations and data management. However, we worked hard to be in the steering position with our end-user customers. The key contracts at Insitu were performance-based and essentially delivered “pixel-hours,” meaning we were paid for imagery delivery instead of flight hours. During my years at Insitu, this was mostly various forms of the military for the U.S. or foreign allies.

Challenges of Each Stage

RD & Engineering

- Fun Quotient. Most people doing a start-up presume they need to be involved in the R&D phase. It’s certainly the sexiest/most fun stage. But the likelihood that someone can add distinctive value at this stage is remote with the thousands of engineers currently pursuing this market.

- Moore’s Law. Everyone knows that Moore’s Law says that things continuously improve. If a team focusing on this area takes too long to develop their new product, others can easily leapfrog them before release. What makes things worse is that every product will be leapfrogged, meaning it’s hard to stay in front.

- Obsolescence. The previous element refers to performance. What is particularly frustrating is that parts of a design become obsolete and are no longer available, which necessitates redesigning the product to accommodate new parts that weren’t backward-compatible. At Insitu, we probably had a dozen such parts causing problems at any one time with nearly a hundred over two years. This is not how anyone prefers to spend their time.

- Product Engineering. R&D is pretty fun. Building a product for end-user use is difficult. I remember that one of my colleagues, who focused on research work in the UAV industry, was shocked to hear that we needed three times the engineers after the design had completed R&D to launch the product and keep it in service. It is hard work getting a product into production and dealing with the constant changes as indicated by the previous two bullets.

Drone Production

- Quality Systems. Creating a reproducible product that meets specification takes a comprehensive quality program. It is exacting, time-consuming, and burdensome. One way to test if an organization is ready for production is to observe the handling of the multitude of electronics during assembly. Are the technicians electrically grounded with protection for static discharge? If not, it’s just an R&D hobby shop. Compliance and testing each step of the way are required.

- Inventory Management. Too little inventory and production schedules or customer opportunities are missed. Too much inventory and the finances are crushed. It’s a fine line to manage the financial performance of production.

- Testing and Measurement. Developing and maintaining a culture of the constant test-measure-improve process does not come naturally. It is hard work.

Flight Operations

- Standards and Curriculum. Providing services with drones is like any other customer delivery service. Standards must exist to ensure a reproducible, high-quality product and a curriculum for developing operators against that standard.

- Hiring and Training. Delivery or drone operations requires putting people into the field who are properly trained and motivated.

- Maintenance. All vehicles require ground maintenance before and after flights. A good estimate would be for every hour of flight, then there should be about X hours of maintenance. The X hours of maintenance occurs cumulatively as the maintenance between each operation and during periodically scheduled maintenance functions, e.g., say every 50 hours. Depending on the complexity and size of the vehicle, X can range from 0.5 to 70. The latter is for full-size helicopter systems. Plus, subsystems could put other preventative and restorative maintenance loads on the operations team.

- Government Compliance. All drone operations require compliance with government regulations related to the airspace but also the theater of operations.

- Logistics. All field operations require the support of parts, materials, maintenance, dispatch, and replenishment. We used to contract out medical support, but there is a multitude of such details.

- Safety and Risk Management. Operating air vehicles not only requires compliance but proactive programs to protect people and property from problems and to minimize the adverse effects when there is a problem.

- Loss of Vehicle. By the nature of the operation, drones are inherently fraught with issues. In the early days at Insitu, we averaged 50 hours between total loss of vehicles. Through continuous quality improvement systems involving hundreds of people, we reduced this to thousands of hours between total loss of the vehicles. Even in this case, the total replacement of a vehicle is a major factor in the operation cost models.

Information Management

- Storage, Conversion, Fusion. Collecting the data from the drone’s sensors can be a challenge. It has to be processed, downloaded, and stored. In many cases, it needs to be fused with other data, e.g., GPS position and time, and then prepped for distribution.

- Security. In many cases, the data and its transmission need to be secure.

- Volume for Analysis. There is a huge amount of data, and some pre-processing to look for changes has long been on the agenda. But unfortunately, most data still needs to be surveyed and analyzed by human eyes. Most data remains unused.

- User-Friendly. A key source of advantage will be the speed and user-friendliness of converting the data into information.

Customer Relationships

- Markets. Capturing customers is a key component of any business. I have noticed that many drone entrepreneurs talk long and hard about the technologies and positioning. But as mentioned previously, the end-user customers are the prime source of funds that are inserted into the value chain. Identifying, cultivating, and winning customers is probably the most critical aspect of the entire process.

- Competitive Response. There will be leapfrogs in technology and changes in business models, but the ultimate challenge is maintaining the customer relationships in the face of a continuous onslaught from new entrants into the field. Developing agility to respond to competitive threats is critical.

Bottomline

Clearly, developing innovation and market leadership in each phase of the value chain is nearly an insurmountable challenge. My advice is to focus on the parts of the value chain for which the most value can be created and protected. However, if I am required to recommend only one phase, I would select Customer Relationships as the most critical and valuable phase of the value chain. Owning these puts the entrepreneur in the best position to optimize the remainder of the value chain through exploiting in-house, outsourced, or partnered resources.

Share this Post