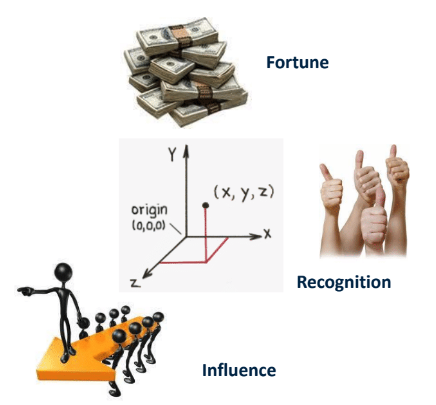

Psychologists spend vast amounts of time developing complex models for how to motivate people. These systems sometimes involve 9 or 12 different parameters. When working with ambitious people over the years, I find that using a three-space model works best for me. It is the most accurate and has the least amount of overlap. In my experience, one or more of the following motivates most ambitious people:

Influence, fortune, and recognition describe what people seek, but you can also think of these in other terms.

- Influence = Prestige or Power

- Fortune = Compensation or Money

- Recognition = Appreciation or Fame

Using these three areas, you can build a model for the person for whom you are trying to motivate, whether it be as a manager or in a negotiation.

Currency of Exchange

A key aspect of any negotiation is determining the currency of exchange. Likewise, a key component of developing and leading ambitious people is developing an effective currency of exchange. Step 1 is identifying what motivates people, even if they themselves don’t know. Step 2 is finding a way that delivers value in the dimension that is important to them in return for the performance, motivation, energy, and followership they might deliver. What it boils down to, in order to be successful when motivating others, you must search for what is important to the other individual.

Influence

People driven by power and influence want others to follow them. Managers and leaders fall into this group. Some want to rise in the ranks as quickly as possible.

If you read NASA Program Management: Case Study in Making the Pie Bigger, you saw an example of one person who was motivated by influence. Jeff, a new NASA manager, didn’t need others to recognize that he was a good negotiator, and he wasn’t in it for the money because NASA doesn’t pay super well. He was willing to sacrifice money and fame to rise in the organization to have others work for him, increasing his power and prestige. The others in the situation received 60% of the programs, initially gaining the power they wanted, but Jeff ultimately garnered enough success that he was promoted and the others then reported to him. It was a strategic chess match that he won.

Fortune

Money drives many people. On the surface, this seems simple enough, but it’s more complicated. One person may be motivated by a bonus at the launch of a new product and another by receiving stock options, which is a tradeoff between risk and reward – the opportunity for a greater long-term gain versus immediate pay. Finding a compensation package that balances near-term, mid-term, and long-term goals for ambitious people can be challenging.

Fortune is the easiest of the three to measure. It should be noted that some people may not really care that much about wealth, but they want an easy way to see how much the company values them, something akin to receiving the highest report card grade.

I remember one situation when an employee was really motivated by money. I went to extensive efforts to explain how we were willing to break our curves for this person since he was exceptional. Later when we had formal HR and they were dealing with an issue, he basically said something to the effect: “Do you know who I am? Have seen how much the company is paying me? You need to pay me a little more respect and dig into this issue for me.” Although the person was comfortable financially, the score relative to others was incredibly important to his view of self-worth.

Recognition

During my time at NASA, recognition from peers, both inside and outside the organization, motivated most of the scientists and engineers I worked with. These people weren’t interested in upward mobility in the organization but wanted to continue developing their technical skills.

For example, when I was a young NASA manager, I knew my scientists were great, but they weren’t getting the recognition they deserved because they were unable to properly communicate their work. In an effort to correct the perception, I signed my senior scientists up for presentation classes. As you can imagine, they were not happy spending four days learning how to create PowerPoint slides and practicing how to present them. But almost immediately, they saw rewards. Within one year, they were leaders in their fields, winning prestigious awards, being invited to workshops and conferences, and reviewing others’ technical work. These events were also helpful to me when I sought more money for our department. My employees were motivated, so our performance increased, which made it easier to receive the funding we sought.

Words of Caution

A common error is when someone confuses what motivates themselves and tries to understand the motivation of others through their own lens. Avoid pushing your values onto others. If money drives you, don’t assume that everyone else has the same desire. Determine what motivates them, and create a model that makes it happen.

When mismatches occur, the opposite can happen. For example, if I tried to motivate a NASA scientist with the promise of taking on additional responsibilities that person would become unmotivated and may leave my team. They really aren’t motivated by taking on additional responsibility and find coordinating others frustrating.

Another example is trying to motivate those who desire influence with money. Personally, I have never been very motivated by money, yet I had several managers early in my career offer compensation rewards rather than putting me in a position of influence. It barely scratched my itch and left me wanting for more.

Most people don’t neatly fall into only one category, but they almost always have a predominant tendency. Once you find out what an employee needs and/or wants to stay motivated and achieve their goals, then you have the opportunity to receive a higher commitment from that employee.

Share this Post